Final prototype and user testing

Observing and getting feedback from real readers.

The prototype is a demonstration of read mode and talk mode, telling (the beginning of) a story about three people living in an old house in a small town. The introduction hints to mysterious things going on, both in the town and in the house itself.

Based on player input, mainly defining the characters, the story is set up in different ways. Each of the three characters have six different variations and backstories, based on two choices: their appearance and an interest. For instance, the character Bea can be a forest ranger, a botanist or run her own cafe. Nils can be a professional e-sports competitor, a drone photographer, robotics expert or a shut in (but friendly) programmer. Esme is your typical friendly granny and a knitting expert, or she can be a retired surveillance officer from the navy.

The listener also gets to choose what floors of the house the characters occupy, which changes the descriptions and appearances of their apartments. Bea the botanist turns the loft into a greenhouse, or she brings the whole garden into the first-floor apartment. Esme the surveillance expert installs radar domes on the roof, or has a secret control center on the second floor. Etc.

After the setup, the prototype enters talk mode, where two characters have a chat. The readers take turns reading “their” character’s dialogue lines, while the other selects how to respond by using emotion buttons.

This is where the prototype ends. Play mode was not included due to time constraints - game design is a big undertaking, a project in itself. In any case, it felt more pertinent to test the other modes.

Read mode

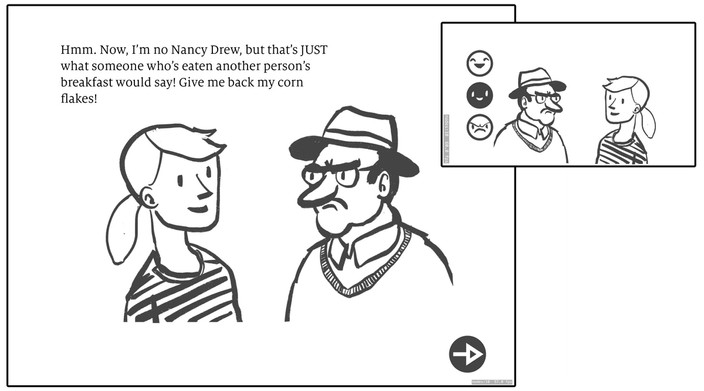

Fig. 6.1 | Screen shot of read mode. Split text/illustration view on iPad, various interactive features on iPhone.

Talk mode

Fig. 6.2 | Screen shot of talk mode.

User testing

Initially I pictured setting up a camera to record facial expressions and body language, accompanied by a voice recorder and screen recordings from the iPad and iPhone. This was not to be. Since the testing would involve children and their parents doing a quite intimate activity, a classic “lab user test” was out of the question.

A strange location would shatter the familiarity of the shared reading setting, and as an observer (stranger or not) my presence could distract the children. They could be overly shy or curious of me as a person, or their attention could drift from reading to watch me taking notes instead. Hidden observation through a camera would be less than optimal, as I feared neither children nor parents would be able to act natural with a lens pointed at them. A hidden camera would be hard to conceal in someone’s home. (Not to mention the creep factor. No spy cameras in teddy bears, please!) Thus, the tests would have to be carried out in the users’ home environments, without me or a camera present.

I would start by introducing myself and the project and tell the participants I’d like to record our conversation with my voice recorder. Then I asked if I could take some pictures and video, and whether or not I could use their names and test data in my report and presentation. Then I’d start the prototype and connect the devices, and ask them to read it together by themselves while I went somewhere else (like the kitchen). I used voice and screen recording to document the shared reading, then ended with an informal interview with the participants, where we further examined and discussed the prototype together.

I only got to do two of these tests. The first dyad consisted of an 10-year old boy and his father, the second of 8-year-old Lotte and her mother Anne-Stine, a teacher and educator at Mjøndalen skole.1 While fewer tests than I would have liked, and far too few to make any generalizations from, they still provided some valuable insights.

Fig. 6.3 | Lotte & Anne-Stine in a “curled-up” dyadic posture (unprompted)

In practice this informal testing worked quite well. By the time we got to the reading, the dyads had more or less forgotten about the voice recorder, giving me quite natural-sounding interactions and discussions. The downside was that the screencasts weren’t telling me a lot, and I would have loved to see more of their faces and body language, as well as the dyadic posture.

If the book is engaging enough, it might overcome the strangeness of a test lab setting, allowing for better documentation and observation, but it seems a bit risky, since you can’t predict the level of engagement beforehand.

The post-reading interview was more useful than I had anticipated. The easiest way for the participants to answer my questions about the prototype, was to demonstrate by playing with the prototype some more. In both sessions, the children were excited for another go2, since they wanted to see what would happen if they picked other options. Neither of the children were particularly shy, so this let me observe their behavior during a reading, and how the dyad interacted with and through the prototype (admittedly, after becoming familiar with it).

I had expected more talk about the story and characters: parents asking about why children made certain decisions or children chipping in their own little ad-libs. The recordings revealed both laughter and some “outbursts” ("OH!"), but the children mostly seemed to listen carefully and deliberate their choices in silence.

In the father-and-son dyad, the father asked the son why he’d placed one of characters on the house’s top floor, to which the son replied that the character had just been described as a loner, and the attic seemed like it would fit him the most. He made that decision while listening to his father reading; at least this time, smartphone interaction was not distracting the child from what was being read.

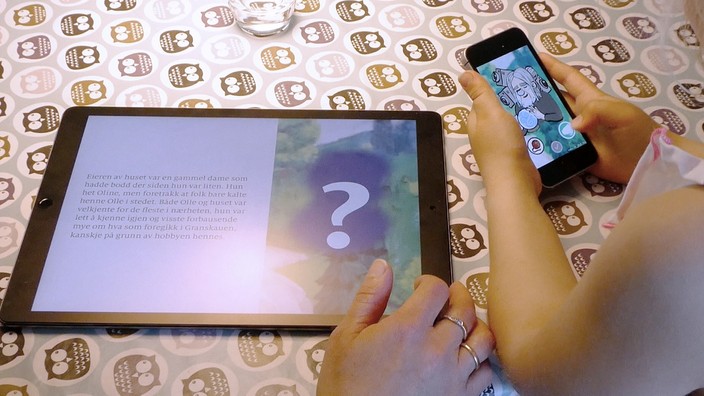

Fig. 6.4 | Lotte choosing the look of a character while listening to her mother read a brief description.

There were some parental scaffolding, with the children asking their parents about some difficult words I’d used. They also seemed insecure making choices, as if they were tested and could give a wrong answer. This required some parental encouragement.

The app led to some confusion on the first play-throughs. The way the text appears in read mode makes it hard to see what paragraph you’ve already been through, and where to continue reading. The children seemed especially confused, but the parents also read several sentences into paragraphs before realizing they’d read them before.

Fig. 6.5 | Testing read mode.

There were also some silences while the users waited for something to happen, interrupted by one of them discovering a progress-button. Progress and pacing proved difficult to control, I observed both children pressing the screen as if to skip their parents’ reading, but they also expressed discontent when their parents turned the page before they were done studying the illustrations.

On consequent play-throughs, the children seemed the most engaged at the times there were buttons to press, with exclamations like “No, I want to do it!” This meant the phone was the most popular with the kids, but in the observations during the interview, I noticed that their focus shifted immediately from the iPhone to the iPad once a choice had been made (fig 6.6). Interviews revealed that they liked that something happened on the iPad by remote control, but also that screen size matters. The iPhone was fine for interactive features, but the illustrations were more interesting to look at on the larger iPad screen, though identical on both devices.

Fig. 6.6 | Lotte focusing on the iPad instead of “her” iPhone.

Lotte also seemed especially interested in seeing what choices her mother would make, whenever they changed roles. At one point, this made her mother hide the screen from her, as if the choice she made was a secret.

Fig. 6.7 | Lotte focusing on the iPhone instead of “her” iPad.

Take-aways

The text intended for reading should not be preceded by earlier text paragraphs. I had thought they made it easier to recall what had happened before, but with focus switching from device to device, they only made it hard to continue reading at the right place.

Pacing and turn orders are difficult, there needs to be clear indications of who has the control, or from whom an action is required. One solution could be to require input from both players simultaneously to progress to the next page, like a button that both players could hold at the same time.

Anne-Stine, the teacher, was excited by the interactive options for shared reading, saying she could definitely picture using something like my prototype with her students in the 1st–4th grades. Creative storytelling (“making stories”) is part of their curriculum, and they often do exercises like mad libs or “one sentence each” with the entire class. They also read books together, taking turns reading out loud. Taking turns also directing the story could make it all the more engaging. The teacher does the scaffolding, asking story related questions to measure reading comprehension.

Anne-Stine questioned herself why she didn’t do more of that kind of scaffolding while reading with Lotte, she said she just didn’t think of it as much when at home. She would like to do it more, but would like to be reminded of if somehow. There’s definitely room to add suggestions for questions and discussions in the text.

Picking out keywords from texts is another important reading skill, something the students practice often. Anne-Stine pointed out that the character selection was a good way to teach it, since the characters’ interests are represented through key objects that shows up in the following subsequent text.

Choices need to be presented in a way that doesn’t make it feel like there are right and wrong answers. The easiest way to do this, is probably by better text prompts beforehand.

Simple interactions can have big payoffs, just hearing her mother start reading about the character Lotte had selected, made her surprisingly excited. Both children seemed inspired by the possibilities opened to them by making choices, and both had a lot of ideas for where the stories could go, from cheetahs in the basement to one of the characters being a secret space alien.

Up next:

Results / final conclusions

Now what? Some quick thoughts to round off the project.

Table of contents

- About project

- Introduction and background

- Research I: Children and media

- Research II: State of the Art

- Divergence

- Convergence

- Final prototype and user testing

- Results / final conclusions