Introduction and background

“The Multiplayer Storybook” explores shared reading on digital devices, and how to design an interactive storybook with a focus on shared reading.

The project concludes in a set of ideas and guidelines for what should be expected and required of such a product, as well as an interactive framework prototype.

An open-ended project from the beginning, it examines current research on shared reading and children’s media, and explores ways in which to apply that research when designing an interactive children’s book. It did not start out as a response to established problems or needs (keeping in mind that they might not even exist), instead looking for possibilities, potential and opportunities through research and testing. The project has followed a (somewhat unpredictable) “design-by-doing” process, explorative in the sense that the specifications for the final delivery were formed during the project, through sketching and prototype work.

The final leg of the project was used to develop a prototype based on these specifications, to test the ideas from this thesis on real users. The prototype is the beginning of a multiplayer storybook, featuring a branching story with interactive role play for two participants, told simultaneously on two devices.

Background

I became a father for the first time just a few months before starting this project (November 2017), and found a new interest in children’s learning and development. I’m curious about children’s books and what goes into making them – not to mention why it seems the digital variety just isn’t living up to its potential.

I hope my daughter grows into one of those children with endless supplies of questions about everything, and I hope I am the kind of dad who’ll always do my best to give her answers. I know: That’s easy for me to say when she hasn’t even started talking yet, but this idea of inquisitive children was what became the starting point for this entire diploma.

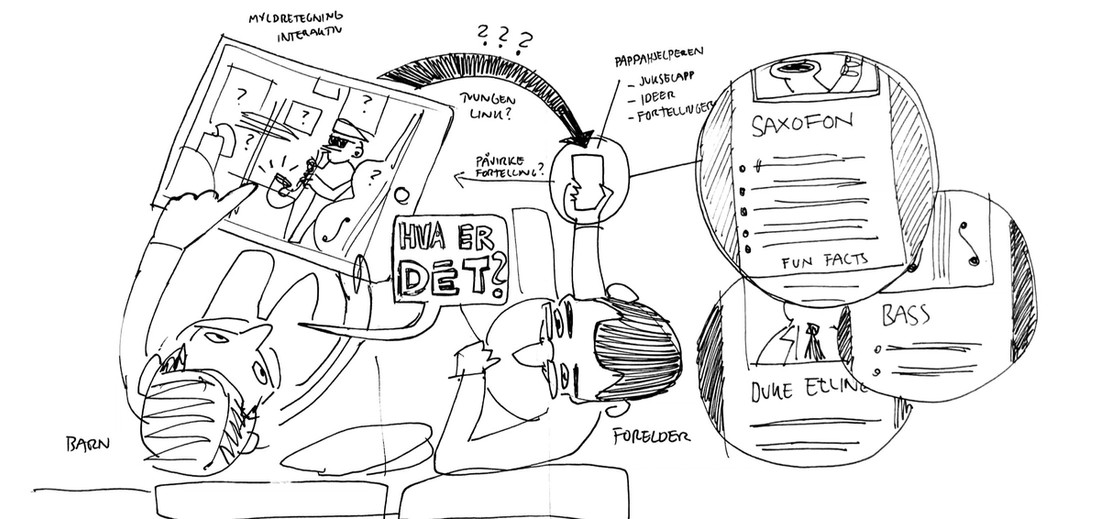

Fig. 1.1 | Project origin napkin sketch, “The Knowing Parent”-app

The very first sketch (fig. 1.1) depicts a child and parent using an iPad app together. The app has a bunch of clickable hotspots (illustrated with a ‘?’), each triggering an action. The parent’s phone acts as the ultimate cheat sheet: displaying fun facts about whatever’s been clicked, ensuring there’s always an answer to “what’s that?” at hand. I won’t say it’s a particularly great idea, but it made me want to take a closer look at digital interactive products for children.

A short history of children’s media

The history of children’s books1 is said to begin with the philosophers Locke and Rosseau some time around the early 1700s. They argued that children were, in fact, different from tiny adults, and should get to read literature appropriate for children – they should have some fun to go with all the morals of the day. Thus, fables became all the rage.

After about a hundred years of hares and tortoises, “Robinson Crusoe” was adapted for children2 and sparked a new genre: the boys-to-men “robinsonades”. European folk and fairy tales also had their golden age in the 1800s, with long oral traditions finally being adapted for children and collected into books by authors like the brothers Grimm and H.C. Andersen.

Girls, as their own audience, were more or less ignored until books like Joanna Spyri’s “Heidi” started appearing in the early 1900s. That really got the proverbial ball rolling, children characters kept becoming more and more well-rounded, often used as critical reflections of their adult surroundings. Eventually (around the 1970s) realism starts creeping in, with child-friendly depictions of war, sexuality, family conflicts and grief.

With all the improvements in print technology during this entire period, illustrations evolved from woodcuts to full-color artwork. Children became a valuable audience, and children’s books started leaking into new media, from magazines and comic books to adaptations for radio, movies3 and television. The 90s influx of home computers brought on the short-lived “age of multimedia”, with children’s books adapted for “edutainment” CD-ROMs.

Neither books nor iPads have become less popular lately4 – children’s media, apps and games are huge industries – but even the most “enhanced” e-books haven’t evolved much from their CD-ROM ancestors. With the technological and computational advances of the last 20 years – just look at computer games, the internet and touch-screen devices – it’s strange that we don’t see more imaginative takes on digital children’s books. What iPad app will be held in the same regard as “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” in 60 years?

Digital children’s books and shared reading

The iPad – for which children’s games, apps and e-books are usually designed for solo use – is notorious for “pacifying” children, with parents and researchers reacting to this still-quite-young medium with optimism and alarm in equal measures. There doesn’t yet seem to be a definite answer to the question: Do iPads help or hamper children’s learning and development?

The one thing “everyone” seems to agree on is that children’s books, no matter the format, aren’t just entertainment — they can have a large and lasting impact on children’s development. They improve general knowledge and understanding about the world, and are important for language acquisition, memory, feelings, motor, social and intellectual skills, and executive function.5

The positive effects of reading are boosted by the presence of an adult. This two-person “unit” of parent and child is often referred to as the “dyad”, and dyadic reading is as important as it is pleasurable: it’s a social activity giving children opportunities to ask questions and discuss the stories, which improves “the parent-child relationship and children’s socio-emotional development6”. Greenhoot et. al (2017) proposes that parent-child interaction “may be critical for helping children to process and retain narratives or other material from storybooks”7.

Interestingly, another study argues that there is no real learning advantage to parental “scaffolding” that can’t be replicated using multimedia. Clever use of animation can be as effective at guiding attention as a parent pointing at things, and whether the text is read by a parent or a recorded voiceover has no bearings on learning or story recall8. If so, shared reading is all about social development: if you need help, it’s healthier to ask your mother than your iPad-app. (At least for now.)

That said, it’s unclear what impact the iPad has on shared reading. Some studies report that digital children’s books “engage and motivate children to practice new literacy skills, such as cooperation, creativity or self- revision.”9 The same studies point to interactivity and animation as potentially distracting and negatively affecting story recall.

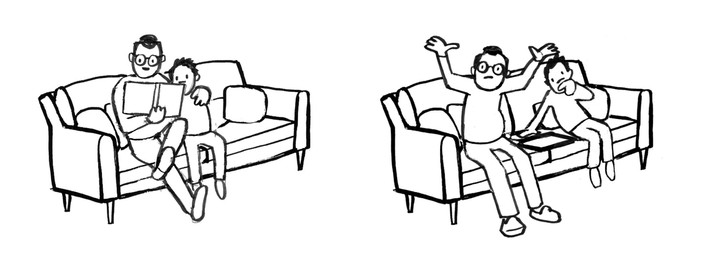

Fig. 2.2 | Left: Shared reading with a traditional (paper) book. | Right: Shared reading with an iPad – how does it work?

Takacs et al. (2014) suggest that digital stories with few interactive features are better for learning literacy skills, while many “are more advantageous for engaging children and prompting physical interaction”10. Yuill & Martin (2016) point out that collaborative activities and shared emotional experiences are all the more important “in a context where digital media could reduce face-to-face sharing.”11

In her article “Is Reading on a Tablet Better for Young Children, or Should They Stick to Paper Books?”, Nicola Yuill has a suggestion for designers that seems relevant to this project:

We believe that designers could think more about how [e-books] can be designed for sharing [...] Book Trust figures report a drop from 86 per cent of parents reading with their five-year-olds to just 38 per cent with 11-year-olds. There is a possibility that the clever redesign of e-books and tablets might just slow that trend.

The decline of shared reading

The trend Yuill refers to is not limited to the U.K., it’s visible in Norwegian statistics12 as well. The time children spend reading books declines sharply around the end of primary school, with a simultaneous increase in their use of digital devices (more than 90% of Norwegian 11-year-olds have their own smartphone). This includes shared reading; fewer parents read with their children when they get skilled enough to read on their own. For Norwegian children, the percentage spending two or more hours with their family per day drops ≈40% between the ages 11 and 13.

Though a significant number of households own iPads13, it seems very few children use them for reading14. Researchers have linked this to the transition to independent reading, which is generally a solo activity – the children are expected to read by themselves15. Nevertheless, many children find shared reading to be a pleasant social activity that they would like to continue.16

Problem definition

Shared reading is a fairly common family activity, and there are plenty of children’s books adapted for and published on tablet devices like the iPad, so where do these fit into the equation? Is there room for iPads in shared reading? Why aren’t they as popular as paper books? Are the apps ill-suited for shared reading, or is it the format? In any case: how can a digital storybook be designed with shared reading in mind? Or in other words: what does a multiplayer storybook look like?

Up next:

Research I: Children and media

Learning about reading, children’s media and trying to figure out what the real academics think about kids using digital devices.

Table of contents

- About project

- Introduction and background

- Research I: Children and media

- Research II: State of the Art

- Divergence

- Convergence

- Final prototype and user testing

- Results / final conclusions