Research I: Children and media

Learning about reading, children’s media and trying to figure out what the real academics think about kids using digital devices.

Reading on paper and screens

Digital natives and new media literacy

There’s nothing novel about tablets and smartphones any longer. Children are “likely to be exposed to technology at times even before they are exposed to print or traditional books”1 and “digital natives” has become a household term. Some parents report that sharing a paper book has become a pleasant novelty2.

Educators are starting to worry less about digital devices negatively impacting learning and development, instead widening the young field of “new literacies” (participatory media like sharing photos and videos, social media, online shopping etc.).

“[...] we regard literacy learning as social in origin and mediated through action and interaction using cultural artefacts. These artefacts evolve over time as societies develop, and in the current era, we argue that literate activity is characterised by the use of both print and digital media. Particularly when using digital devices, meanings can be expressed through multiple modes of symbolic representation, such as combinations of spoken and written language, images, icons, sounds, layout and animation.”

Trans-literacy

Trans-literacy is the idea that skills gained from reading in one medium, translates to other media.

Reading e-books promotes traditional literacy skills and is particularly supportive in the area of vocabulary development, and young children’s interaction with enhanced digital books also advances their facility to communicate and comprehend across modes and platforms, sometimes called trans-literacy development.

This would suggest that if you want children to become book-readers, there are advantages for digital narratives to stay close to a book-like format. Trans-literacy is not only promoted by similarities between printed and digital reading environments, it is also important for children to learn the differences between them3.

Why digital devices are bad

It seems almost intuitive, at least for those of us who were introduced to tablets and smartphones as grown-ups, to view digital devices as potentially harmful. One study found mothers to have a strong “preference for reading on paper, whether this was reading themselves or for their child”, while their children don’t really care that much. It also found that the mothers reading paper books made more story-relevant comments with a higher “interaction warmth” than when reading digital books4.

Several studies point out how interactive features, though engaging, are often distracting. This usually means it affects story recall negatively, i. e. the child is too busy clicking buttons to remember what the story was about later. Interactive features can even cause “cognitive overload” in young children when they have to switch between listening to a story, getting words explained, and playing games – all within a few moments5. Some educators also worry apps and games lead to addiction and over-stimulation, as well as having “negative consequences for the kinds of patient and persevering learning dispositions needed for the occasionally arduous process of learning to read and write.”6

Children touch and press everything, and features that were designed to be in the background can suddenly become foregrounded7. Glitches, bugs and interface quirks can become fun toys on their own. For instance, a cool page turn animation can end up being more interesting than what’s on the page itself. Marsh et al. argues that this is a new type of play that only happens on digital devices. They call it transgressive play, “in which children contest, resist and/or transgress expected norms, rules and perceived restrictions in both digital and non-digital contexts”8.

Why digital devices are good

The pairing of text narration and multimedia elements strengthens verbal comprehension and story recall by reducing cognitive load (younger children aside)910. This is true for both single and shared reading, and taken advantage of in pre-schools, schools and at home11.

Teachers report that iPads can help children with motivation, consentration, and classroom communication. It also facilitates “collaborative and independent learning in playful and creative ways.”12

[...] well planned literacy-related iPad activities stimulated children’s motivation and concentration, and offered rich opportunities for communications, collaborative interaction, independent learning and enthusiastic learning dispositions. [...] immediate feedback, along with tangible and satisfying end products, motivated children to engage deeply with iPad-based literacy activities, which as one practitioner commented, attracted their attention like ‘bees to a honeypot’

Animations are better for explaining difficult words and concepts than still illustrations – some words, especially verbs, really benefit from some motion. Music and sound effects can also be important when depicting more abstract expressions or emotions and feelings13, for instance a sad-sounding minor harmony.

Parent-child interaction

Shared reading

As mentioned earlier, shared reading is about the social connection and interaction between parent and child. In broad terms, this interaction consists of parents’ “scaffolding” (guidance) and discussions around story, illustrations and interactive elements.

Several studies1415 suggest that illustrations generally make parents and children interact more with each other, both verbally and non-verbally. (In some cases, the lack of illustrations make parents compensate by reading with more emotion.) Illustrations are very effective at capturing children’s attention to the stories being read to them, and help “familiarize children with situations that they might otherwise reject”. When the dyads have illustrations to talk about, it’s easier to keep the children interested and focused, leading to strengthened story recall. (Surprisingly, anthropomorphic illustrations and language are the exception, leading to lower levels of learning16.)

The parent and child’s body language and their positions relative to each other is called “dyadic posture”.

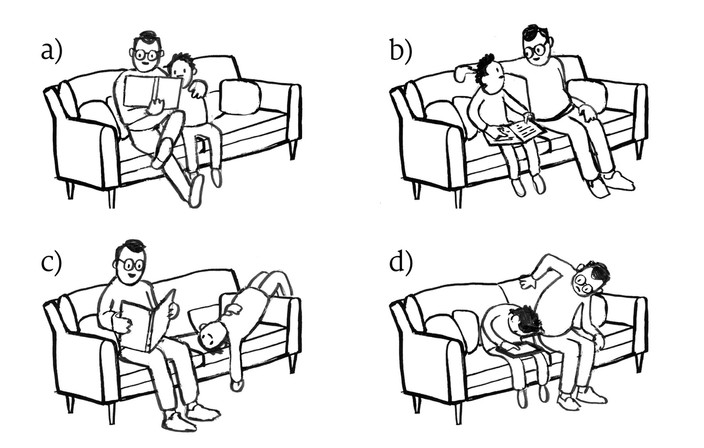

Fig. 2.1 | Shared reading and dyadic postures.

(Fig. 2.1) illustrates some typical dyadic postures during shared reading. The first is the “curled-up” position, where the dyad sit close to each other while looking at the same page. This occurs whether the parent (fig. 2.1, a) or child (fig. 2.1, b) is reading out loud. When the child is reading, the parent may participate by “scaffolding”, i. e. guiding, providing help and information.

The second posture (fig. 2.1, c) occurs when there’s nothing but text on the page (or illustrations are non-essential), and comfort matters more than proximity. Typically when a parent reads a storybook to the child:

[...] when a mother read from paper, she often held the book between herself and the child, with the child very close to her, either tucked under her arm to facilitate visual sharing or in a very relaxed posture with audio sharing, but little sight of the book.

On-screen shared reading on a tablet device (fig. 2.1, d) is known to present some challenges, related to children’s perceived “ownership”17 of the tablet as a medium, and their closeness to the screen obstructing their parents’ view of what’s happening on the display.

When children read from a screen, they tended to hold the tablet in a ‘head-down’ posture typical of solo uses [...] leading [the mothers] to curl round behind the child in order to ‘shoulder-surf’ the screen, rather than adopting the ‘curled-up’ position common when reading the paper book.

Games and play

There have been several broad classifications of the ways children play. A couple of famous ones, Roger Caillois’ definitions from 1961 and Corinne Hutt’s categories from 1979, more or less agree18 that the main groups are:

- Games for learning, or epistemic play

- A variety of role play, or ludic play, where children draw from their experiences – from their own life, fantasy and drama (TV, movies etc.)

- Games with rules, play based on skills or chance, often competitive

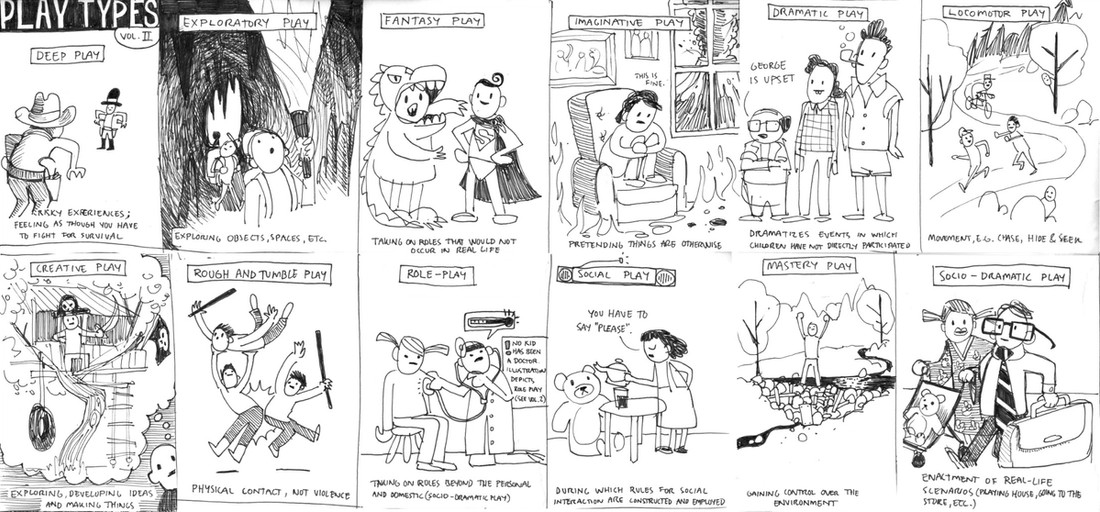

Hughes’ taxonomy of play from 2002 expand these into to 16 play types that can be used to describe most activities children are engaged in19. The study “Digital Play: a new classification” (Marsh et al., 2016) updates Hughes’ taxonomy for “on-screen” play, and adds a 17th play type that “occurred when children used features of the apps that were not part of the design, thus transgressing the app producers’ intentions”. (Something to look out for!)

Fig. 2.2 | Some of the play types from Hughes’ taxonomy

The authors argue that there is no play type that cannot be replicated digitally, with detailed examples of iPhone-games turning into life-and-death situations. Comparing it to traditional play:

[...] contemporary digital cultures provide rich opportunities for the promotion of play that is rooted in children’s everyday experiences. This is not [...] an inferior form of play; rather, it sits alongside more traditional play activities and is important for creative development

The list goes a long way to explain the popularity of games like Minecraft, in which most of the 16 types are catered to, from mastery of environments to various kinds of role play. I found Hughes’ taxonomy and Marsh’ new classification to be very handy both for reference and inspiration, as I could generate ideas by going through the play types and think of ways to apply each one to my own storybook.

Up next:

Research II: State of the Art

What else is out there, and is it any good?

Table of contents

- About project

- Introduction and background

- Research I: Children and media

- Research II: State of the Art

- Divergence

- Convergence

- Final prototype and user testing

- Results / final conclusions